All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Relations between Health Perception and Physical Self-Concept in Adolescents

Abstract

Background:

Self-rated health is influenced by personal characteristics, such as gender and age. Similarly, it seems that physical self-concept can influence this perception, being positively related to healthy habits and quality of life. Adolescence is a sensitive stage in establishing the physical self-concept as well as in health-related behaviours. Therefore, it is necessary to study these relationships since the behaviours established at these ages will have a lasting impact on life.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to analyse the relation between physical self-concept and self-rated health in adolescents.

Methods:

A sample of 1697 adolescents (824 boys; 48.5% and 873 girls; 51.5%), aged between 12 and 16 years old (14.2 ±1.0) participated in the study. For data collection, a questionnaire was used. The measured variables were perception of health, physical self-concept and gender. A chi-square test was used to analyse the data and evaluate the association between the variables, and Cramer´s V was used to quantify the degree of association. A Classification and Regression Tree (CART) evaluation was applied to discover the influence of the variables that have an effect on the perception of health.

Results:

The results show that boys perceive to have better health and greater physical self-concept than girls. Similarly, a positive relationship has been found between the health´s perception in both genders and the physical self-concept, in each of its subdomains.

Conclusion:

A positive relationship has been found between health perception and physical self-concept. Therefore, an increase in the physical self-concept is presented as an opportunity to improve health self-perception, which can positively affect the health of young people.

1. INTRODUCTION

Perception of health and physical self-concept are two complex constructs that have been identified as conscious reflection processes, which enable people to evaluate different aspects that surround them [1, 2]. Perception of health is a subjective and reliable indicator of a person’s general state of health [3, 4], which extends to biological, psychological and social aspects [5]. On the other hand, physical self-concept is the compilation of perceptions that people have of themselves, reflecting the attributions made with regard to their conduct. This includes the concept they have of themselves as a physical, spiritual and social element [6, 7]. At the same time, experiences with other people are taken into account, shaped by comparison with others and their opinion of them, all of this influenced, in turn, by gender, age and the Physical Activity (PA) carried out [8]. Both concepts can condition people’s personal development and wellbeing [9], especially at a time of personal growth and maturity, such as in adolescence.

Perception of health in adolescents refers, to the presence or absence of illness and the general understanding of the “self” [10]. Adolescence is a period in life that is identified by the absence of illness and in which a positive perception of health is usually shown [11-14]. However, evidence of differences with respect to gender has been found; it would seem that girls perceive themselves as having a poorer state of health in comparison with boys [15-17]. This is probably because perception is linked to personal, sociocultural, behavioural and psychological factors [18].

With respect to physical self-concept, four subdomains or dimensions can be distinguished [19]: sports competence, physical condition, physical attractiveness and strength. Its development takes into account a mixture of different elements, with participation in physical activities being one of the most influential [20]. This is why, in different studies, it has been demonstrated that boys who participate in physical activities regularly show a better assessment of physical self-concept with regard to their skill and physical condition than girls [21, 22]. Similarly, it would seem that physical activity can positively influence perceived physical attractiveness [23, 24], although, in this case, no differences with relation to gender were found [25].

A joint analysis of the two constructs establishes that as physical self-concept increases, so does a positive self-perception of health [26]. Similarly, both show a positive relationship with quality of life [27], academic performance [28] and healthy lifestyle habits [20], thus contributing towards forging adolescent self-esteem [29].

Bearing in mind that adolescence is recognised as being a crucial period for health promotion strategies, as this is a time when decisions that have a long-term impact are made [30], it is vital to address all of the aspects that in one way or another influence the development of a healthy and active lifestyle. A closer examination of the relationship that can be established between perceived health and physical self-concept in adolescents will enable intervention strategies aimed at establishing healthy lifestyles to be defined. An analysis differentiated by gender is also necessary, insofar as girls are affected before boys, or the changes that occur are more visible in girls. For this reasons, differences can be seen, with regard to both perception and behaviour.

The aim of this study was to analyse the relationship between physical self-concept and perceptions of health in a group of adolescents, with an awareness of possible differences, bearing in mind gender as a decisive variable of the differences recognised.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

1697 secondary school pupils took part in the study: 824 (48.56%) boys and 873 (51.44%) girls, with ages ranging from 12 to 16 (14.2±1.0).

The pupils were selected using a purposive non-probability sampling method in 22 schools in Galicia (Spain). In these schools, at the time of data collection, a plan to promote physical activity managed by the regional government (General Secretary’s Office for Sport. Xunta de Galicia) was being developed.

2.2. Variables

The variables included in the analysis were perception of health, physical self-concept and gender.

For perception of health, we used the question: how would you rate your state of health? The possible answers were: (1) Not good, (2) Normal, (3) Good, (4) Very good. For the data analysis, the responses were classified in the categories “a good perception of health” and “not a good perception of health”.

The different levels of physical self-concept were [19]: sports competence, physical conditioning, body attractiveness and physical strength. Starting from these subdomains, we clustered the questions [31], which remained as follows:

2.3. Data Collection

The International Questionnaire on Students’ Lifestyle was used as the data collection instrument (CIEVA in Spanish). Previous studies confirmed the usefulness of this instrument in the age range of the sample [32-35]. A validation and adaptation process into Spanish was carried out [36]. It is comprised of 39 questions set out in four categories: (1) personal information (6 questions); (2) lifestyle (12 questions); (3) attitudes and perceptions (12 questions), (4) assessment of school, physical education and participation in a sporting or physical activity (9 questions). Cronbach’s alpha was used as a measure of internal consistency, obtaining an acceptable value for the entire questionnaire (α = 0.78) as well as in each of the categories (α > 0.78).

2.4. Procedure

Prior to the data collection, an informative letter was sent to each of the schools participating in the study explaining its aims and the procedure to be followed. Each school sent this information on to the parents and legal guardians, requesting pupils’ voluntary participation. Once informed consent was given in writing, the questionnaire was administered to the participants by teachers during Physical Education classes and accompanied by a member of the research team. The completed questionnaires were then collected and sent back to the research team to be analysed.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis to characterise the sample using percentages and frequencies was carried out, transforming the perception of health variable into a dichotomous variable (perception of good health or perception of not good health). Subsequently, the association between perception of health and physical self-concept was evaluated through Chi-Square tests, differentiating this analysis by gender. Cramer’s V was used to quantify the degree of association between variables, bearing in mind that values between 0.06-0.17 indicate a small effect, between 0.18-0.29 a medium effect and above 0.30 a large effect [37].

To finish, a multivariate analysis was performed using the decision tree technique to distribute the participants in accordance with their perception of health and physical self-concept. This test identifies the combination of physical self-concept subdomains that best predict the perception of health in adolescence, also providing visual information on the impact that each independent variable has in a hierarchical tree model [38, 39].

Two decision trees are put forward, with a TRC algorithm being applied for each of the genders. In both cases, a three-fold cross validation method was used, fixing the number of minimum cases at 100 for the parent nodes and 50 for the child nodes.

The different analyses were carried out using the statistical software SPSS 21.0 for Windows (Spss Inc. IBM, USA) with a significance level of P<0.05.

3. RESULTS

In Tables 1 and 2, the results relating to the boys’ and girls’ perception of health and physical self-concept are described. Around 70% of the boys and just over 55% of the girls are shown to have a good perception of health. The boys and the girls, with better levels of physical self-concept have a better perception of their state of health.

In the case of the boys with a good perception of health, being satisfied with their appearance, being fit and being fast are given good or very good assessments. In the case of the boys with a bad perception of health, being agile and strong are the most highly valued subdomains.

The girls with a good perception of health are more closely identified with being agile, fit and satisfied with their appearance. When they have a bad perception of health, being agile and strong are the more highly valued aspects (Table 3).

|

Subdomains (Fox & Corbin, 1989) |

Variables (Piéron, telama, Naul & Almond, 1997) |

|---|---|

| Sports competence | Athletic qualities |

| Physical condition | Lightness and elegance, agility, fitness and speed |

| Physical attractiveness | Thinness and satisfaction with its own appaerance |

| Force | Force |

| Variable | Health Perception | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Not good | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | X2 | P | V | ||

| I have good athletic qualities | Nothing | 10 | 1.2 | 19 | 2.4 | 111.999 | 0.000 | 0.378 |

| Little | 30 | 3.8 | 52 | 6.6 | ||||

| Medium | 120 | 15.3 | 85 | 10.8 | ||||

| Quite | 165 | 21 | 56 | 7.1 | ||||

| Much | 218 | 27.8 | 30 | 3.8 | ||||

| I am light and elegant | Nothing | 7 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.8 | 57.021 | 0.000 | 0.271 |

| Little | 28 | 3.6 | 42 | 5.4 | ||||

| Medium | 160 | 20.6 | 98 | 12.6 | ||||

| Quite | 207 | 26.7 | 62 | 8 | ||||

| Much | 136 | 17.5 | 29 | 3.7 | ||||

| I am agile | Nothing | 9 | 1.1 | 10 | 1.3 | 52.815 | 0.000 | 0.259 |

| Little | 24 | 3.1 | 36 | 4.6 | ||||

| Medium | 113 | 14.4 | 68 | 8.7 | ||||

| Quite | 195 | 24.8 | 87 | 11.1 | ||||

| Much | 201 | 25.6 | 42 | 5.3 | ||||

| I am fit | Nothing | 8 | 1 | 18 | 2.3 | 128.192 | 0.000 | 0.405 |

| Little | 27 | 3.5 | 46 | 5.9 | ||||

| Medium | 101 | 12.9 | 91 | 11.6 | ||||

| Quite | 188 | 24.1 | 57 | 7.3 | ||||

| Much | 217 | 27.8 | 28 | 3.6 | ||||

| I am fast | Nothing | 11 | 1.4 | 14 | 1.8 | 87.385 | 0.000 | 0.334 |

| Little | 24 | 3.1 | 40 | 5.1 | ||||

| Medium | 109 | 13.9 | 74 | 9.4 | ||||

| Quite | 173 | 22.1 | 79 | 10.1 | ||||

| Much | 227 | 29 | 32 | 4.1 | ||||

| I am strong | Nothing | 11 | 1.4 | 8 | 1 | 16.571 | 0.002 | 0.146 |

| Little | 40 | 5.1 | 31 | 4 | ||||

| Medium | 131 | 16.7 | 76 | 9.7 | ||||

| Quite | 197 | 25.2 | 71 | 9.1 | ||||

| Much | 164 | 21 | 53 | 6.8 | ||||

| I am very thin | Nothing | 7 | 0.9 | 17 | 2.2 | 59.475 | 0.000 | 0.276 |

| Little | 48 | 6.1 | 49 | 6.3 | ||||

| Medium | 219 | 28.1 | 108 | 13.8 | ||||

| Quite | 188 | 24.1 | 38 | 4.9 | ||||

| Much | 80 | 10.3 | 26 | 3.3 | ||||

| I am satisfied with my appearance | Nothing | 15 | 1.9 | 23 | 2.9 | 101.640 | 0.000 | 0.360 |

| Little | 27 | 3.4 | 40 | 5.1 | ||||

| Medium | 68 | 8.6 | 67 | 8.5 | ||||

| Quite | 143 | 18.2 | 54 | 6.9 | ||||

| Much | 293 | 37.3 | 56 | 7.1 | ||||

| Variable | Health Perception | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Not good | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | X2 | P | V | |||

| I have good athletic qualities | Nothing | 18 | 2.2 | 69 | 8.3 | 125.325 | 0.000 | 0.389 | |

| Little | 57 | 6.9 | 84 | 10.2 | |||||

| Medium | 155 | 18.7 | 140 | 16.9 | |||||

| Quite | 128 | 15.5 | 47 | 5.7 | |||||

| Much | 110 | 13.3 | 19 | 2.3 | |||||

| I am light and elegant | Nothing | 8 | 1 | 33 | 4 | 53.122 | 0.000 | 0.253 | |

| Little | 49 | 5.9 | 68 | 8.2 | |||||

| Medium | 165 | 19.9 | 141 | 17 | |||||

| Quite | 166 | 20 | 76 | 9.2 | |||||

| Much | 81 | 9.8 | 41 | 4.9 | |||||

| I am agile | Nothing | 9 | 1.1 | 27 | 3.2 | 68.910 | 0.000 | 0.287 | |

| Little | 37 | 4.4 | 59 | 7.1 | |||||

| Medium | 135 | 16.2 | 148 | 17.7 | |||||

| Quite | 159 | 19 | 89 | 10.7 | |||||

| Much | 131 | 15.7 | 41 | 4.9 | |||||

| I am fit | Nothing | 6 | 0.7 | 43 | 5.2 | 136.687 | 0.000 | 0.405 | |

| Little | 65 | 7.8 | 92 | 11 | |||||

| Medium | 125 | 15 | 151 | 18.1 | |||||

| Quite | 152 | 18.2 | 58 | 6.9 | |||||

| Much | 121 | 14.5 | 21 | 2.5 | |||||

| I am fast | Nothing | 10 | 1.2 | 31 | 3.7 | 73.016 | 0.000 | 0.296 | |

| Little | 50 | 6 | 85 | 10.2 | |||||

| Medium | 144 | 17.2 | 122 | 14.6 | |||||

| Quite | 146 | 17.5 | 93 | 11.1 | |||||

| Much | 122 | 14.6 | 32 | 3.8 | |||||

| I am strong | Nothing | 21 | 2.5 | 31 | 3.7 | 21.425 | 0.000 | 0.161 | |

| Little | 64 | 7.7 | 83 | 10 | |||||

| Medium | 161 | 19.4 | 113 | 13.6 | |||||

| Quite | 147 | 17.7 | 91 | 11 | |||||

| Much | 76 | 9.2 | 43 | 5.2 | |||||

| I am very thin | Nothing | 10 | 1.2 | 36 | 4.3 | 45.346 | 0.000 | 0.234 | |

| Little | 58 | 7 | 80 | 9.7 | |||||

| Medium | 209 | 25.3 | 145 | 17.5 | |||||

| Quite | 126 | 15.2 | 66 | 8 | |||||

| Much | 64 | 7.7 | 33 | 4 | |||||

| I am satisfied with my appearance | Nothing | 22 | 2.6 | 68 | 8.1 | 82.974 | 0.000 | 0.315 | |

| Little | 41 | 4.9 | 62 | 7.4 | |||||

| Medium | 84 | 10 | 88 | 10.5 | |||||

| Quite | 127 | 15.2 | 64 | 7.6 | |||||

| Much | 197 | 23.6 | 83 | 9.9 | |||||

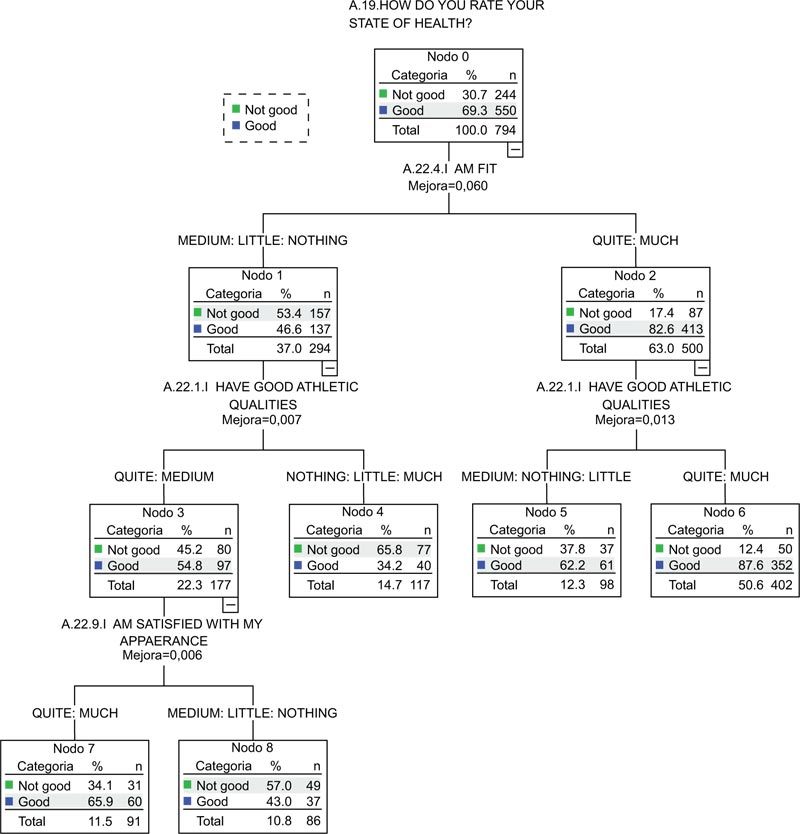

In the case of the boys, the results of the multivariate analysis showed a decision tree made up of 8 comparison nodes; 2 level 1 nodes established with regard to physical condition, 4 level 2 nodes established with regard to sports competence and, lastly, 2 level 3 nodes established with regard to physical attractiveness. The overall percentage prediction was 75.4% (Fig. 1).

At the start, we found that the tendency of the boys is to perceive that they have good health (n = 550, perception of good health = 69.3%). Perception of fitness was observed in level of influence 1, where it was seen that the adolescents who assess their fitness level more highly (node 2, perception of good health = 82.6%) perceive themselves as having a better state of health than those who assess their fitness level negatively (node 1, perception of good health = 46.6%). In the group that assesses their fitness level the most highly (node 2), the influence of sports competence was observed, where the group that has the best perception of their sports competence (node 6) are those who perceive themselves as having better health (perception of good health = 87.6%) than those who did not assess their sports competence positively (node 5, perception of good health = 62.2%).

On the other hand, and returning to the level of influence 1, we can see that those belonging to the group that assesses their fitness the most negatively (node 1) are influenced by sports competence, with the appearance of two groups, one with a low assessment and the other with a very high one (node 4), the latter perceiving themselves as having worse health (node 3, perception of good health = 34.2%) than those who assess their sports competence with average or good levels.

For its part, physical attractiveness influences node 3, where it is seen that those who hold satisfaction with their appearance in high esteem (node 7) perceive themselves as having better health (perception of good health = 65.9%) than those who are not satisfied with their appearance (node 8, perception of good health = 43%).

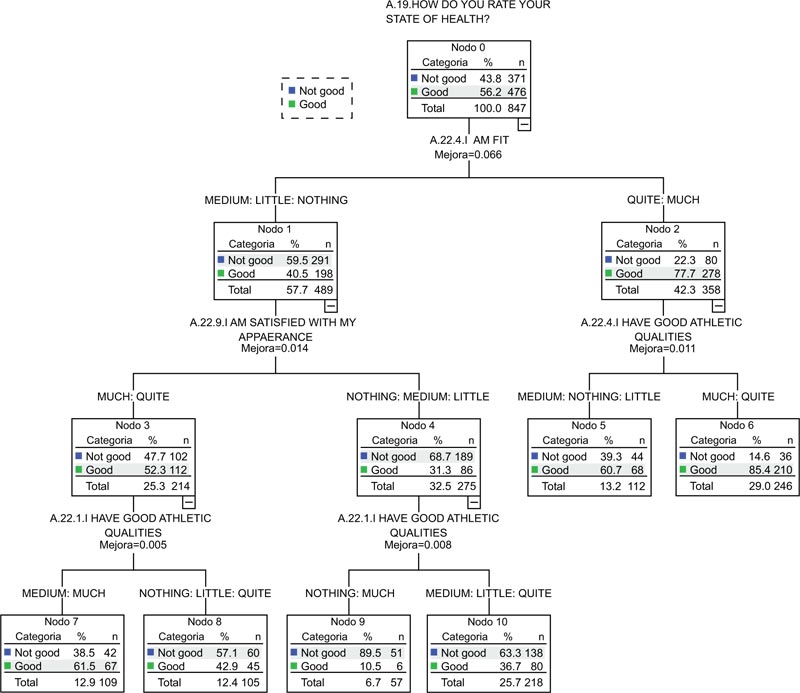

Ten comparison nodes were created for the girls; 2 level 1 nodes were established with regard to physical condition, 4 level 2 nodes with regard to sports competence and physical attractiveness and, lastly, 4 level 3 nodes with regard to sports competence. The overall percentage prediction was 70.1% (Fig. 2).

Initially, the girls perceived themselves as having good health (n = 476, perception of good health = 56.2%). Perception of fitness was observed in the level of influence 1, where it was seen that the adolescents who assess their fitness level more highly (node 2, perception of good health = 77.7%) perceive themselves as having a better state of health than those who assess their fitness negatively (node 1, perception of good health = 22.3%. In the group that assesses their fitness level most highly (node 2) the influence of sports competence is observed, where the group that has the best perception of their sports competence (node 6) are those who perceive themselves as having better health (perception of good health = 85.4%) than those who do not value their sports competence positively (node 5, perception of good health = 60.7%).

On the other hand, and returning to the level of influence 1, we can see that those belonging to the group that assesses their fitness level the most negatively (node 1) are influenced by their physical appearance, with two groups appearing; those who are satisfied with their appearance (node 3), who perceive themselves as having better health (perception of good health = 52.3%) than those who are not (node 4, perception of good health = 31.3%).

Lastly, in the third level, the influence of sports competence in girls who are not satisfied with their appearance can be observed, the adolescents who have a more extreme opinion, either positive or negative, being those who perceive themselves as having the worst health (node 9, perception of good health = 10.5%), with a higher percentage being seen when perception of their sports competence is average (node 10, perception of good health = 36.7%).

In the same way, in the group that felt satisfied with their appearance (node 3), the influence of sports competence also exists; in this case, when such sports competence is perceived positively (node 7, perception of good health = 61.5%), the perception of good health is greater than in the negative case (node 8, perception of good health = 42.9%).

4 DISCUSSION

The aim of this research was to identify the relationship that exists between perception of health and the different physical self-concept subdomains in a group of adolescents, taking into account gender as a determining factor of the differences that can be seen.

A greater focus placed on this age group as well as an analysis differentiated by gender can contribute to a better evaluation of this problem area, identifying, understanding and acting with regard to the causes and inequalities that can perpetuate themselves and that will eventually determine future health.

The results reveal that the boys show higher values, both in the perception of health and the different physical self-concept subdomains, coinciding with what has been seen in the previous studies [4, 40, 41]. In general, adolescence is hard for everyone, but girls seem to enter it earlier and could be affected earlier by changes, or such changes might be more evident, or they might feel more exposed. Along the same lines, girls are subjected to greater levels of stress and greater concern over their appearance, social relationships and body weight [42].

The analysis of the relationship between perception of health and physical self-concept determined that the more positively physical self-concept is valued, the better the perception of state of health. In the same way, this positive relationship was found for each of the physical self-concept subdomains. These results are consistent with what has been seen in other studies [43].

Seeing the influence that physical self-concept has on the perception of health, and this being a strong predictor of actual health [3, 4], it is important to know which factors influence this physical self-concept, so that by increasing them, we can achieve an improvement in self-perceived health. Thus, the existence of a positive perception of physical and mental health provides a high level of satisfaction with life [44], affecting adaptation and favouring personal and social development [27].

Another of the determining factors in forming physical self-concept is doing Physical Activity (PA), whose positive influence increases the more PA is done [45, 46]. Furthermore, this influence will be greater when physical activity is established as a life habit [46]. It would, therefore seem imperative to promote PA as a means of boosting adolescents’ physical fitness and health.

On a social level, boys and girls of this age are subjected to pressure and a high degree of worry about their physical attractiveness, influencing both genders in their opinions on physical self-concept. Boys are affected more by aspects related to physical condition, strength and sports skills [47] but, on the other hand, girls seem to be more worried about aspects related to physical attractiveness [48, 49]. In this way, the formation of physical self-concept will depend on the influence of these factors, strength and personal ego, carrying more weight in the perception of boys and physical attractiveness in the perception of girls [47, 48].

Bearing in mind the study’s limitations, such as the impossibility of establishing cause and effect relationships, as well as the impossibility of identifying the differences between the start and end of adolescence, it would be interesting to evaluate aspects such as BMI and socioeconomic status. BMI could have an influence on sports competence and physical attractiveness when an inverse relationship is demonstrated, girls being subject to greater influence [41]. Similarly, socioeconomic status could be related to more and better opportunities, making it possible to satisfy individual needs and interests.

On the other hand, the strength of this study lies in that it boasts a greater sample than that recruited in previous studies and the use of multivariate statistical analysis methods that allow a better understanding of the determining factors involved in the perception of health [50].

Although it would seem that the relationship between self-perceived health and perception of physical self-concept is positive, more studies need to be carried out in order to illustrate this knowledge, focusing on the reasons that can impact the formation of these perceptions, making it possible to act in this respect in order to improve quality of life at such an important stage as adolescence.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study emphasise the positive relationship that exists between perception of health and physical self-concept. Therefore, an increase in physical self-concept presents itself as an opportunity to improve self-perceived health, which will have a decisive impact both on the future health of young people as well as on their quality of life as adults.

An evaluation differentiated by gender is necessary to enable us to identify, understand and take action with regard to the causes and inequalities that can perpetuate health problems and dissatisfaction with life.

Future studies should deepen into the differentiated assessments made by boys and girls. In this sense, a qualitative methodological proposal that allows identifying and understanding the singularity and specificity of behaviors based on gender would be interesting. Thus, the development of proposals and strategies could have a specific action on the problem studied.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the General Secretariat for Sports of the Xunta de Galicia (regional government), Spain.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals were used in this research. All human research procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Prior to the participation in the study, parents or guardians were informed about the purpose and nature of the study and written informed consent was obtained.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.